I recently received my newest edition of “Columbia” magazine by the Knights of Columbus. An article was about a Knight who received the Congressional Medal of Honor. Unfortunately, besides a little about the prayer life of the man who received the medal, the Knights did not delve deeper on the morality and justness of the war in Afghanistan, especially after Osama bin Laden was killed (of course, in Pakistan and not Afghanistan), which is when the events occurred for this sailor to receive the award. Instead, we just got platitudes about defending freedom and doing your duty. Are my brother Knights of the Prince of Peace or Knights of the Military–Industrial Complex? Christ told us it would be hard to follow Him; it is too easy to go along to get along in general society, which celebrates militarism and war.

Category Archives: CAM Original Articles

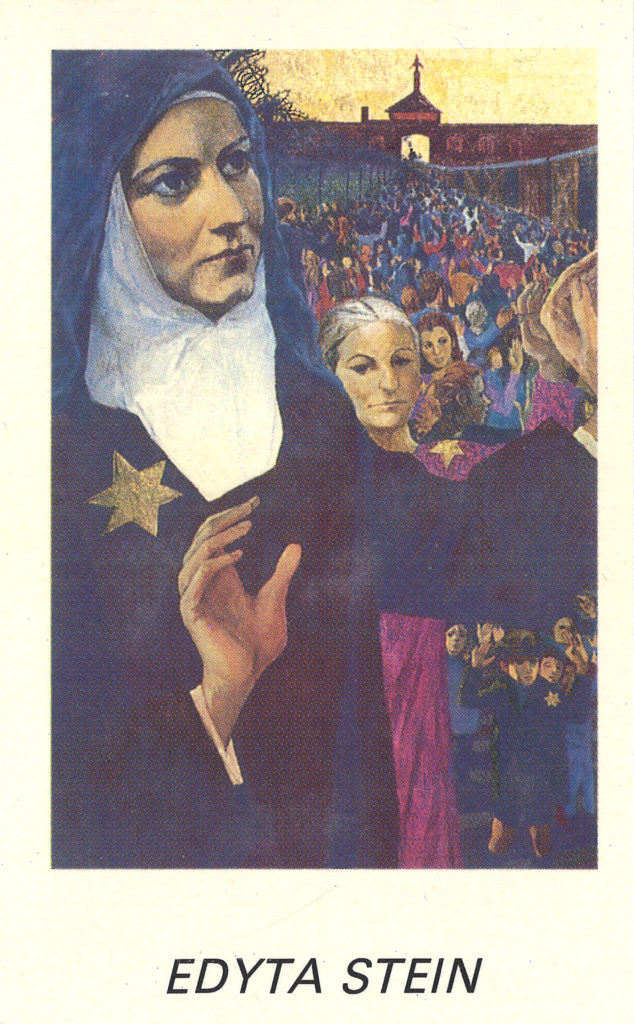

The Miracle of Edith Stein

Today’s podcast is about St. Edith Stein and the miracle that led to her canonization on Oct. 11, 1998. That miracle happened back in 1987 to the daughter of our frequent guest on the podcast, Fr. Emmanuel Charles McCarthy. Twenty-one years ago today, Fr. McCarthy con-celebrated the canonization Mass of Edith Stein in Rome with Pope Saint John Paul II (pictured below). I am excited to share this story of a miracle, which is always a story of hope. Moreover, my wish is that this story has the same affect on you that it did on me: It prompted me to take another look at Fr. McCarthy’s life and his life’s work, and to take more seriously that message of nonviolent love of friends and enemies which he has spent his life trying to communicate to the Church.

In an interview with EWTN about her book Edith Stein: A Spiritual Portrait, author Diane Marie Tartlet says: “[Edith Stein’s] whole life was an adventure and she realized that our life of the faith is not boring. If we really have surrendered ourself to God, every day becomes one of surprises, one where we are realizing God’s presence in others in our lives in various situations. There are no coincidences.“

The story of the miracle of Edith Stein illustrates in a vivid and compelling way these truths about “the life of the faith,” specifically the life of faith of Emmanuel McCarthy. Listen to the podcast today and you will understand that the story of the miracle of Edith Stein begins years if not decades before the medical anomaly of 1987. You will walk away believing that, indeed, “there are no coincidences.” The connection between Fr. McCarthy and Edith Stein was no doubt planned, encouraged, and inspired by God, and what happened to two-year-old Theresa Benedicta McCarthy in March of 1987 was nothing less than a kind of pinnacle in, or culmination of, the life of the faith that her father had lived: The miracle seems to have been linked with Fr. McCarthy’s ability to see God at work in certain situations, and his willingness to live a life that, like Stein’s, went deep into his faith, entailing sacrifice, surrender, and surprise.

Unfortunately, in the interview with EWTN, there is no mention of the miracle that made Theresa Benedicta of the Cross, Saint Theresa Benedicta of the Cross. And perhaps at first glance, that is not surprising: Ms. Tartlet wrote a book about what Edith Stein did when she was on Earth. Maybe she didn’t have the time in the interview to discuss what she did from heaven. Maybe she didn’t know.

But similarly, in this lecture on Edith Stein given by Father Barron, now a Bishop in the American Catholic Church, there is no mention of the young American girl whose miraculous healing led to Edith Stein’s canonization. And maybe at first glance, that’s no surprise either. It is only a ten-minute video after all.

Now in this lecture about Edith Stein given at Boston College, the lecturer does mention (in an aside) that some of in the audience might have heard of the young girl, Benedicta McCarthy, who was miraculously healed through the intercession of Edith Stein, and that she interestingly enough lived right there in Boston at the time; but he does not mention the fact that her father was a Catholic priest, also born and raised in Boston, who had given his life to preaching and teaching the ways of peace, just as Edith Stein had said she wanted to give her life for peace. He had even been nominated for a Nobel Peace Prize. You would think that background to the miracle might be, well, something of note.

If you have been listening to the podcast since we started publishing it back in May, you know that we frequently talk about Gospel Nonviolence with Fr. McCarthy, and the fact that this message — the message of Jesus’ nonviolent love of friends and enemies, which Jesus preached by word and by deed — seems unwelcome in the institutional Church. Many times on the podcast we have discussed the strange ways (which become obvious once you have “eyes to see”) that the institutional Church de-emphasizes, minimizes, or cuts out this message of nonviolent love entirely, leaving most Catholics ignorant of it, if not outright hostile to it.

Seen in this light, the act of omission of the background of the miracle of Edith Stein, and its connection with Fr. McCarthy, an American priest, by those Catholics who want to talk about Edith Stein seems to me — how shall I say? — not entirely coincidental or accidental. Can you imagine if the canonization of a saint resulted from the miraculous healing of the daughter of, say, the founder of 40 Days for Life? Do you think anyone on EWTN, when talking about that saint, would fail to mention that miracle?

In the podcast, Fr. McCarthy tells the story of when EWTN flat-out rejected the video below when he sent it to them years ago, because, they said explicitly, their channel only airs “Catholic content.” The video below is a conversation between a Catholic priest in good standing with the Church (Fr. McCarthy), another Catholic priest in good standing who was the Catholic Chaplain to the bomb crews who dropped the bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki (Fr. George Zabelka), and Mairead Corrigan Maguire, a 1976 Nobel Peace Prize recipient — a pretty stellar line-up! The description is as follows: “Coming from different backgrounds and witnessing injustice and violence first hand, each participant describes how they were converted to Gospel Nonviolence. They also discuss the urgent need for the Christian Churches, Catholic, Protestant, and Orthodox, to return to Jesus’ teaching of nonviolent love of friend and enemy.”

According to EWTN, this is “not Catholic.”

In my opinion, this is “a problem.”

Part of the story of the miraculous healing of Fr. McCarthy’s daughter Benedicta through the intercession of Edith Stein (Saint Theresa Benedicta of the Cross) must include the ways in which the Catholic media has chosen not to explore this side of the miracle: the fact that it happened to the daughter of a Catholic priest who has been more or less ostracized by the institutional Church for teaching Christian nonviolence — for decades — and the ways in which that Church fails to educate people about this aspect of the Catholic faith.

As a result, we did not have enough time in the podcast to talk about Edith Stein herself to the extent that I wanted to, though we did talk about her life a bit. In the end though, there are many resources, books, websites, videos, for learning more about the holy person of St. Edith Stein, her radiant intellect, her painful conversion (in the sense that it upset her mother), her empathetic heart, the adventure of her life and her tragic death at the hands of Nazis. (Many if not most of those Nazis, we must not forget, considered themselves Christians, and for some reason never had eyes to see the glaring contradiction between following the Prince of Peace and supporting the atrocities of the Third Reich, either by their words, their deeds, or their silence. Must we not ask ourselves if Edith Stein’s martyrdom was not one result, of similar millions, of the Catholic Church’s failure to preach Jesus’s message of nonviolent love of friends and enemies for 1,700 years?). I suppose I felt I had to use the time on the podcast to try to address the strange and enduring lacuna: that part of the story of the miracle that is rarely, if ever, told, the “before” of the miracle — the decades worth of a life lived in faith which led to that moment of healing and the glorification right here on Earth of God’s omnipotence and His infinite mercy.

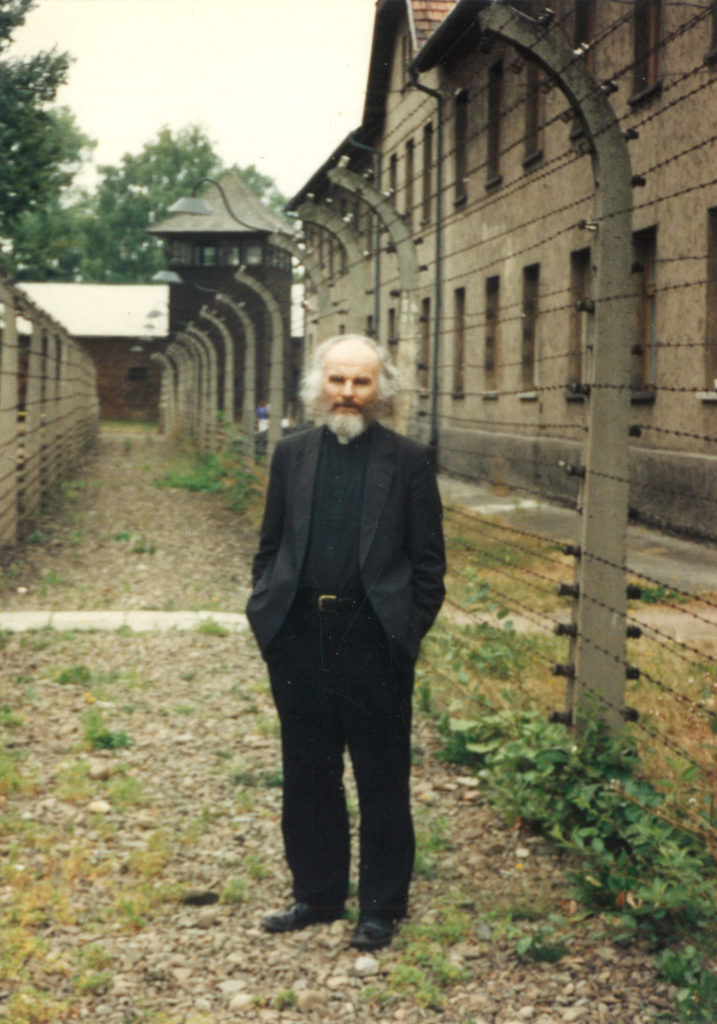

There is an “after” to the miracle, too, which seems to me a bit sad and disappointing. Yes, Fr. McCarthy did have the opportunity to con-celebrate the canonization Mass with Pope Saint John Paul II in 1998, but the miracle has not opened the eyes, ears and hearts of many Catholics in the way it could — in the way that it opened mine, or I should say the miracle has not been allowed to open the eyes, ears, and hearts of many Catholics in the way that it could, mainly because the Catholic press, especially in America, has been and continues to be absolutely uninterested in reporting on it, and continues to treat nonviolent love, which was the love of Edith Stein, which was the love of Jesus Christ, as merely an odd, infrequent and eccentric choice on the part of exceptional or exemplary Christians rather than as a central tenet of Jesus’s teaching, not to mention the oldest tradition and teaching on violence in the Catholic Church.

It wasn’t until I saw the ABC News Special called “It Takes a Miracle” that I began to wonder if I shouldn’t pay a bit more attention to this Father McCarthy character. It remains sad to me that I had to find out about this miracle, and its connection with this priest, through a secular media outlet, and from an old bootlegged copy of the ABC special on a CD in a dusty jacket, handed to me by a friend of Fr. McCarthy’s, rather from my own Church. At the time of this writing, the YouTube video of the ABC special only has 184 views, and the dynamite conversation (rejected by EWTN as “not Catholic”) only 277! Imagine what would happen if EWTN and National Catholic Register and other such outlets would merely allow its viewers to consider the tradition of Gospel Nonviolence in a serious and studious way!

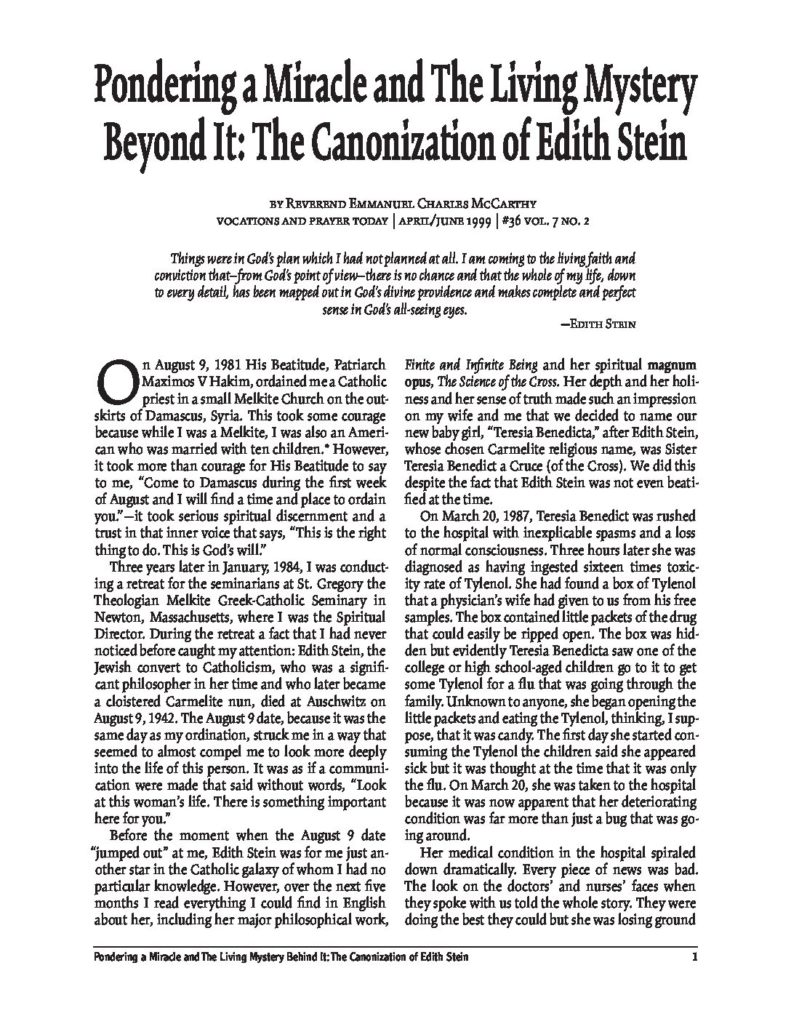

In addition to listening to the podcast, I highly recommend watching the ABC News special (above) as well as reading the one thing Fr. McCarthy ever wrote about the miracle: “Pondering a Miracle and the Living Mystery Beyond It” (below). More resources on Edith Stein can also be found here at the Center for Christian Nonviolence.

Finally, below are some photographs that Fr. McCarthy has allowed me to share with you. In her interview with EWTN, Tartlet says:

“[Edith Stein’s] whole life was an adventure and she realized that our life of the faith is not boring. If we really have surrendered ourself to God, every day becomes one of surprises, one where we are realizing God’s presence in others in our lives in various situations. There are no coincidences. She almost says it’s a pity for those who are content to live a life of superficiality. Because once you start going deep, life becomes an adventure.”

The interviewer nods and responds: “But many people are afraid to go deep because they are afraid of what their adventure might be.”

One wonders if, by omitting, minimizing, or flat-out rejecting Jesus’ teaching of nonviolent love of friends and enemies, EWTN and other mainstream Catholic media outlets are themselves spreading a “superficial” Christianity because they are “afraid to go deep,” and afraid of what that adventure might be.

Saint Theresa Benedicta of the Cross, pray for us! Pray that we can follow your example in ceaselessly seeking the truth, that we never be satisfied with anything less than the truth, and that the Christian Churches will return to Jesus’ teaching of nonviolent love of friends and enemies, and thereby find the true peace of Christ, and bring that peace to the world.

Befriending Strangers

How are we to deal with people who come to us from the homes they have left behind?

These people are strangers to us at first. He or she is the Unknown Person and at this point we know practically nothing about this Stranger. Maybe we know something of his or her homeland’s reputation or maybe all we know is what this person looks like to us. Until there is initial contact there is no real knowing of the person and no meaningful shift can begin toward “de-strangerizing” the Unknown Person. Before we can actually know the Stranger as a fellow human being it is all too easy to project our own fears onto that person.

Perhaps the most common thing to imagine, as well as perhaps the most understandable, is to see the Stranger as a threat. This is a bit of ancient survival programming we have inherited courtesy of our distant ancestors. We modern people might be tempted to Boo and Hiss at our primitive ancestors for burdening us with this innate fearfulness but let’s not. Instead let’s honor them because the truth is that without their survival skills we wouldn’t be here to reflect on this issue. We, their descendants, need to recognize that bit of ancient programming for what it is: A once-upon-a-time necessity. The mistake that we must avoid now is to use this relic of human programming as if it is today’s cutting edge technology.

One of our characteristics as human beings is our inherent capacity to transcend our primitive instincts. We are built to learn and grow from our mistakes and slowly evolve toward becoming more enlightened beings. As a species, we are a work-in-progress, thousands of years into a process that is still quite incomplete.

Growing up requires us to move beyond our primitive Fear-based orientation to life. We need to mature into a Love-based orientation to living in our world. Embracing a Love-based mode of being and interacting does not mean that we no longer get scared. We cannot simply delete the old programming. Like it or not, it is part of who we are. What it means is that we no longer have to be limited by fear as we live our lives. As we increasingly move into a more mature level of consciousness we have greater access to our intrinsic capacity for Love-based interactions with others.

None of this means that we suddenly throw all caution to the wind. It means that we move through our situations with appropriate care based on a rationality that naturally emerges from healthy love.

As we return to our hypothetical Stranger, we need to make contact with this as yet Unknown Person in order to have actual observations to take the place of our primitive fear-based fantasies. A meaningful question to consider is: How shall we choose to initiate contact with the Stranger?

The most reasonable way to make contact with Strangers is to welcome them as potential friends. Yes, we still need to be aware of possible dangers and observe proper caution as we start making contact but this choice represents the best way to utilize our own freedom for maximum advantage. If we initiate our encounter with the Stranger in a benevolent fashion the probability is that the Stranger will reciprocate. If we treat him or her as a threat it is likely that he or she will respond to our fear with fear of their own and start seeing us as a threat as well. This ultimately leads to preparation for the anticipated attack.

Perhaps our greatest “sin” is our willingness to de-humanize and demonize our fellow human beings. Under the right conditions it becomes tempting to reduce the Different Other to some sort of Offending Impediment to our way of life. Part of this temptation may also include a component of righteousness that can (and too often does) reach the level of the Arrogant Assumption that one is “doing God’s will” by de-humanizing the Different One. There is, however, something vitally important that needs to be recognized: It is entirely possible to escape from the prison of fearing and hating the Different One and emerge into what can legitimately be called a state of recovery. This involves an initial process of step-back-from Untruth and then a step of move-toward Truth. At first this recovery can be understood as a growing awareness and conscious rejection of the lies previously assumed to be truths: the mental-trap illusion of “Us vs. Them” and the associated false belief that there just isn’t enough of what we all need so someone will have to do without (“and it’s not gonna be us!”). It is also becomes a process of discovering what is actually true and consciously moving in that direction: every one of us is very human and we are not nearly so different or separate from each other as we once thought. There is also enough for all of us if we are willing to let go of our fear and the greed that emerges from it.

Our fear of the Stranger is solvable and it is solved by becoming aware of the Truth. The Truth, in this case, comes as the answer to the question of who we and the Stranger really are. In each case the answer is the same. Each of us, without exception, is a Sacred Child of the Ultimate Mystery. We all come from the same Original Source of Creation regardless of whether one prefers to think of this as the story of the cosmic “Big Bang”, the Genesis story or any of the countless creation stories human beings have been sharing with each other for thousands of years. If we can accept this perspective, the Stranger is nothing more than someone at a costume party who has not yet taken off their mask and allowed us to see their true face. It may help them to do so if we are willing to show them our true face first.

Finally, it is not so much a question of who the Stranger is but rather a question of who we are and what kind of people we want to be in relation to that Stranger. What are our intentions? Do we want them to be afraid or do we want them to feel welcome?

How would we want to be treated if we were the Strangers?

That Which Divides Us

That we are a divided people is not breaking news.

Our divisions are reflected back to us every day. We are consistently presented with the forced-choice of our social, political and religious identities. One belongs to a particular social class and not others. One is either a “conservative” or a “liberal”. One is a “Christian” or a “Jew” or a “Muslim” or a “Hindu” or a “Buddhist” or some other religious label. These are just a few of the ways we identify ourselves. Somehow it became very important to label ourselves and each other. Perhaps this helps us stay with the illusion of “knowing” who we are.

There is another form of division that transcends the “usual suspects” of the various labels already described. This is the division between the opposing agendas of materialism and spirituality. One of the central features of these differing agendas is the question of whether or not violence is deemed acceptable as a means of solving problems. This question also correlates with the contrasting views of separation and connection. Materialism emphasizes the separateness between each of us while realistic spirituality focuses on the connections we share with each other and our world.

The materialistic perspective attributes the highest priority to creating, selling and acquiring Things. This view asserts that the centrality of Things is what life is really all about. In this framework, people are a means to an end. This is sometimes known as “productivity”. If one is “productive” in the proper way then one is recognized as a valuable person. One is considered an “asset”.

The spiritual perspective embraces a very different orientation. It holds to the belief that it is not things that have significant value but rather it is Love and Life itself that is truly valuable. People are to be loved and things are to be used. This perspective is grounded in the belief that all life is inter-connected and inter-related rather than separate and in a state of competition.

This division becomes most apparent in terms of those who are willing to use violence to get what they want and those who refuse to resort to violence to achieve their goals. When a person, when life itself, is seen as a means to an end it becomes acceptable, even laudable, to control, exploit or destroy if that’s what it takes to reach a goal. Domination and destruction are contradictory to the goals of healthy spirituality.

When life is considered sacred it can no longer be objectified as simply a means to an end but instead is known and related to as part of the infinite manifestation of Love.

We can belong to the World of Things or the World of Love. We cannot avoid this choice.

Why focus on the contrast between violence and nonviolence? This framing points to the question of how human problems are to be solved. It is the desire to solve our problems that unites us while it is the methods for achieving those solutions that causes us to diverge into the contrasting problem-solving forms of violence (materialistic power) and nonviolence (spiritual power).

The exercising of Materialistic Power essentially says: “Comply or die.” This “death” may be quite literal or it may be metaphorical in terms of deprivation of needed resources or basic freedoms. It is the straightforward imposing of physical force or intimidation on a person or group to induce their obedience.

The exercising of Spiritual Power, on the other hand, presents a perplexing set of refusals and active responses. When operating from a sense Spiritual Power a person refuses to “fight fire with fire” with the oppressor, refuses to run away from threatened harm, refuses to disengage from the oppressor and refuses to comply with the oppression process. Essentially a person acting from this orientation says: “I won’t fight with you on your level. I won’t run away from you. I won’t end my relationship with you and I won’t obey your unethical manipulations.” The active response is at least as perplexing. While under siege from the oppression of Materialistic Power the active response from one grounded in Spiritual Power is an unwavering “I love you.”

Violence exists as a broad spectrum of attitudes and actions. Its trademark is in its seeking to dominate and diminish the Other who is always regarded as quite separate from the perpetrator of the violence. It seeks victory by destroying or controlling the Other who is defined as a threat of some sort. Its manifestation may take the form of a physical attack with weapons designed to amplify the intended destructive power of the attacker. It may also take the form of a more subtle, non-physical attack (e.g. character assassination) that can nevertheless produce devastating results.

Violence as a process can also be understood as a projection of a person’s pain and/or fear. If one has not dealt constructively with these experiences the temptation to disown them becomes very powerful: “I will hurt you so that you will have to deal with my pain and I won’t. It will become your pain. I will scare you so that you will have to deal with my fear and I won’t. It will become your fear.”

There are those who believe in the use of violence as the method of choice to solve a broad range of human problems. If the end result is sufficiently valued then the means are considered justified. Counted among these believers are women and men, young people and old people, the wealthy and the not-so-wealthy, liberals and conservatives and the full spectrum of religious labels. Those who accept this kind of problem-solving are represented across a wide range of ethnic, social and economic backgrounds. There are law-makers and law-breakers, from the local level to the international stage, who subscribe to the idea that the end justifies the means and that this is how problems get solved.

There are also people from all of the groups just named who completely reject the notion that violence is an acceptable method for solving human problems. They maintain that the means to the desired end cannot be contrary in nature of that end: War cannot create Peace, Oppression cannot create Freedom, Hatred cannot create Love. This group holds that the Means and the End are inseparable.

Nonviolence can be best understood as the active expression and demonstration of love and not as the mere absence of destructive attitudes and actions. When we speak of love it is easy to go off on some wild goose chase as to what this really means. The love conveyed in active nonviolence is a kind of sacrificial love. This is the kind of love that consciously chooses to accept and endure real suffering for the sake of another, specifically for the sake of healing the perpetrator. This kind of love does not define the perpetrator as the “enemy” who must be destroyed or defeated. Instead, Sacrificial Love seeks to help the perpetrator become aware of the truth of his or her real inter-relatedness to the person or people he or she is hurting. In traditional language, it is the deep truth that we are all brothers and sisters to each other.

No less an intellect than Albert Einstein stated: “We cannot solve our problems with the same thinking we used when we created them.”

If we give credence to Einstein’s claim about the nature of problem-solving it becomes logically impossible to believe that the problem of violence, whether this is a problem between nations, between individuals or within ourselves, can be solved through violent methods. The time has come to free ourselves from the mental prison that holds us in the insane belief that declares: “We have to kill people who kill people to show them that killing people is wrong.”

It becomes necessary to change our way of thinking and understanding in order to solve our problems. It is necessary to shift our awareness and our perspective in order to successfully solve our problems. We cannot solve our problems with the same low-level thinking that got us into trouble in the first place. If our house is burning down we cannot save it with a flame-thrower!

The problem of violence within ourselves is a crucial one. As previously stated, if one does not successfully heal his or her inner violence and the injuries from it then one will be very likely to project this destructiveness onto someone else. It is necessary to establish this internal healing as the foundation to solving human problems on an interpersonal level as well as between various social groups.

No less a wisdom teacher than Jesus of Nazareth explained metaphorically that one must first take the wooden beam out of one’s own eye before attempting to remove the splinter out of another’s eye. (Luke 7:5)

If we are to take him at his word, this means that we need to start healing our own impairment and suffering in order to stop perpetuating violence against ourselves which is often invisible to the rest of the world but the individual (who, in this case, is both perpetrator and victim) is acutely aware of his or her own internal self-torture process (e.g. “I’m such an idiot!”, “I’ll never be good enough!”, “No one would want to be with me if they knew what I was really like.”, etc.). We need to attend to our own healing and make peace within ourselves before we start telling, coercing and demanding that the other person (or group or nation) act a certain way to put their house in order.

What divides us is a faulty perception of how separate we are from each other. This misperception supports the belief in the “win-lose” form of problem-solving in our lives. When all we see is our disconnectedness is becomes easy to assume that competition in the only way to achieve needed solutions.

We move from division to unity when we start to see that the truth of our existence is one of connection and belonging. What were once seen as major differences between one another can now be recognized as largely superficial. We begin to love more and more inclusively as we realize that any injuries we do to others we do to our selves and that the compassion we extend to others is also the compassion that we receive.

A Sheep Among Wolves: “Hacksaw Ridge”

Copyright © 2016 Ellen Finnigan

Originally published on November 4, 2016 on LewRockwell.com.

A Sheep Among Wolves

Desmond Doss was a real man but he seems more like the stuff of legend. Being a bit of a loner, small in stature, and meek, he was probably the last person anyone would ever peg for a potential war hero. He enlisted in the Army during the second world war because he believed in the cause. He only had one condition: He would not carry a gun. Make that two: He would not work on Saturdays. Though he did not receive an extensive formal education as a young man in West Virginia, he did receive excellent spiritual formation as a member of the Seventh Day Adventist Church: He took the Ten Commandments seriously, all of them, without exception or qualification, including “Thou Shalt Not Kill” and “Keep Holy the Sabbath.” He wanted to serve his country but a way that was consistent with the Way (the Truth and the Life). He wanted to be a medic. The military assigned him to a rifle company, naturally, figuring the heat of peer pressure would iron him out. Clearly they did not know the depths of character, courage, and conviction in Desmond Doss. They could not yet imagine how a man who refused to touch a gun could put up such a fight!

The incredible Hacksaw Ridge, the new film directed by Mel Gibson, tells amazing story of Desmond Doss, his decision to enlist, his difficult training and his unbelievable feats on the battlefield, for which he was eventually awarded a Congressional Medal of Honor. I attended an advanced screening of the film and had dangerously high expectations. I’m a Gibson fan, and I’d heard the film had received a 10-minute long standing ovation at the Venice Film Festival. I had watched the 2006 documentary based on Doss’s life, The Conscientious Objector (available on YouTube), and enthusiastically assigned it to my honors students after we read The Iliad and the The Aeneid this fall, thinking I had found the perfect thing with which they could compare-and-contrast the pagan idea of heroism.

With a few small reservations, I thought the film was excellent, but I have a few predictions as to how it will be received by the Catholic media, which has disappointed me in the past. My prediction is that the Catholic “Right” will promote this film under the banner of “religious liberty”, the Catholic “Left” under the cause of “conscientious objection,” but I believe both are reductive and shortchange the complexity of the film and the person of Desmond Doss. The “religious liberty” camp thinks that the great postmodern struggle is between Christians and secular society, but it was not the atheists, socialists, humanists, or communists who put Desmond Doss through hell in the military, who insulted him, persecuted him, and uttered every kind of evil against him, falsely. It was his fellow God-fearing, red-blooded Americans, whom we can assume were mostly Christians. While the other men were flipping through nudie mags in the barracks, Doss was studying Scripture. At first they dismissed him as a hick, a prude, a coward; grown men would throw shoes at his head while he was trying to pray. He was eventually ostracized, humiliated, harassed, and even beaten. His superiors tried to get him discharged for mental illness. They court martialed him. One soldier even threatened: “If you try to go to war with me, I’ll shoot you myself!”

“I don’t think I could have taken it,” said one man who knew Desmond Doss at boot camp. “I would have told them all to go to hell! But Doss—he never got angry.” In the documentary, his comrades recall Doss’ gentle demeanor, his lack of interest in retaliation, and his unwavering commitment to personal prayer. The actor who plays him, Andrew Garfield, should win an Oscar. He portrayed perfectly the endearing earnestness, quiet strength, and undeniable mystique of this most unusual man. Vince Vaughn adds the perfect touch of humor in his role as a sergeant who doesn’t hate Doss so much as find him incredibly exasperating. When Doss’ superiors would snarl and ask who the hell he thought he was and why he thought he was so special and why he wouldn’t just go home, Doss would respond, humbly, by saying that in a world that was falling apart, he didn’t see anything wrong with someone trying to put a small piece of it back together. He wanted to serve his country. He wanted to serve them.

And this is where he doesn’t quite fit the profile of the typical “conscientious objector.” When the military tried to send him to a conscientious objector camp, he insisted on going to war! Doss believed that the United States was fighting for freedom, including religious freedom, and that it was an honor to serve his God and his country. He wanted to serve–but in a way that was consistent with his beliefs. His beliefs were very simple: He couldn’t picture Jesus killing people, but he could picture Jesus with a first aid kit. He preferred to be called a “conscientious cooperator.” He thought he could be just as good a soldier as anyone else, only: “Where other people are going to be taking life, I’m going to be saving it.”

This is what makes him a hero for our times. So many folks try to say that going to war or not going to war, which is always couched in terms of defending something or not defending something, is a choice between “doing something” and “doing nothing.” It’s the old false dichotomy of fight or flight. Either you fight, or evil runs rampant in this world. Jesus did neither and Desmond Doss shows us that a third way is possible. One of my favorite anecdotes in the documentary is when Doss says that his superiors tried to convince him of the errors of his ways by posing an age-old question, a hypothetical akin to: “What if someone was raping your grandmother and you had a gun?”

Desmond Doss replied simply: “I wouldn’t have a gun!

And that’s the truth.

To the screening they invited people from the religious community as well as the military community. The publicists who introduced the film explained, in warm, beige tones, that it was a film about faith — and heroes. Polite applause. It is understandable that marketing execs would want to cast as wide a net as possible, but to say that this is about faith is to gloss over the obvious challenge it presents to people of faith. Faith in what? In the words of Rev. Emmanuel Charles McCarthy, the central question of all religion is: What kind of god is God, and what does God expect of us, if anything? The fact that Desmond Doss answers this question differently than his fellow Christians is the very thing that creates the conflict at the center of the story; it is the engine of the drama. We don’t watch Hacksaw Ridge, rapt, in order to find out if our hero will successfully vanquish the enemy, because our hero for a change has absolutely no interest in that, either the enemies he faces on the battlefield – the “Japs” – or the enemies he creates in his own tribe. We watch to see if our hero will be defeated and defeat seems likely: Either he will stand by his convictions, run onto the battlefield, and lose his life (in this world), thereby proving he is a fool, or he will pick up the sword, save his life (in this world), and admit that his convictions were foolish. What other outcome could we reasonably expect? What other outcome could we possible imagine?

“Nobody can understand what he did on that ridge,” said one of his comrades, “nobody.” I could talk to you all day long and you could never understand it. You would never believe it.”

In Guam, stories began to circulate about a medic who would doggedly pursue the wounded and try to help them– no matter what. (He was eventually allowed to go into battle as a medic unarmed.) It didn’t matter who they were, how badly they were wounded or how badly they had treated him. Doss would help them, often ignoring the rules of triage. His motto was: “As long as there is life, there is hope.” But the depths of bravery, compassion, and fortitude in Desmond Doss weren’t fully comprehended until Okinawa, where his actions on “Hacksaw Ridge,” a 400-foot cliff so named because of the Japanese ability to chop up Allied forces and spit them out, became legendary, maybe even miraculous.

After the screening, a man who was a friend of Desmond Doss’ spoke to us and assured us of the film’s accuracy. I trust it is accurate, but it didn’t strike me as complete. Obviously, every screenplay has limitations. They can’t include everything, but there are things in the documentary that were left out of the film, or at least not highlighted in the film, and they are important to understand the full picture.

In the film, Doss is shown being incredibly brave under fire, but the filmmakers do not convey just how impossible it was for him to survive or to do what he did. He was one of three men to hang the cargo net from the ledge of the Hacksaw Ridge. He volunteered. (In the film, if I remember correctly, he arrives and the net has already been secured.) You see: to hang the net was impossible, because you would have to get up on the ledge where the Japanese had clear lines of sight from their fortified positions. To maximize your chances of survival, you had to stay low to the ground, crawl, and even then, your chances were scant. There is a photograph of Desmond Doss standing up — silhouetted — on the ridge. He didn’t get shot. The guns were silent while he was up there. Why? How? Nobody could explain it.

The net allowed the Americans to scale the cliff, from which point they could try to take the ridge. They climbed up and got driven back down twice before they succeeded. On top, it was a bloodbath. Not only did Desmond Doss run out time and time again into enemy fire, defying all odds of being shot and killed, or captured and tortured, but as a man of slight stature, he did what Arnold Schwarzenegger couldn’t do in his heyday: He singlehandedly dragged and/or carried 75 men from up to 125 feet away to the cliff, secured them with a special knot, and lowered them down – again, singlehandedly — over the 400-foot cliff to safety. He saved 75 men in twelve hours, which meant he saved one man every 10 minutes. Desmond Doss’ friend who spoke at the screening said that Desmond once told him that after he had carried and lowered the first three men, he had absolutely no physical strength left. None. He just kept repeating the prayer: “Please, Lord, let me get one more. Please, Lord, let me get one more.”

The speaker at the screening also told us that Andrew Garfield, who played Desmond Doss, who is a lanky guy like Doss, was taught the “fireman’s carry,” which is the way Doss would have been trained to carry big, heavy, injured, helpless men. After the first few takes, they had to call in a stunt double. He wasn’t strong enough to pull it off take after take after take. As one of Doss’ comrades pointed out, many soldiers receive the Medal of Honor for one act of extreme bravery in war; but in Doss’ case, the Medal was awarded for things he did over and over and over again. There are stories about a Japanese soldier who remembered having the American medic in his crosshairs; when he went to shoot him, the gun jammed. There are stories of Japanese soldiers being found with American bandages on them.

What was happening on that ridge? How were these things possible? Could it have something to do with what Desmond Doss, as conscientious cooperator, was cooperating with, rather than what he was objecting to?

Rev. Emmanuel Charles McCarthy begins his book All Things Flee Thee for Thou Fleest Me* with a quote by Jacques Ellul:

“God intervenes radically only in response to a radical attitude on the part of the believer – radical not in regard to political means but in regard to faith; and the believer who is radical in his faith has rejected all means other than those of faith.”

The question of violence is a question of means. Desmond Doss probably shared many of the same ends as other soldiers of faith: to stop evil, to stop evil from spreading, to save lives, to bring about peace, to save his soul, to get to heaven. But the difference between Desmond Doss and the other soldiers is that Desmond Doss rejected all means other than those of faith, specifically faith in the God, the God who is Love. This is because the Seventh Day Adventist Church had taught Desmond Doss that the means of violence were not available to him as a Christian and were not compatible with Love. When mainstream Catholics understand this about Desmond Doss, they understand at once that he is an “other” kind of Christian, with a different faith. Is it a different faith?

This is another important question.

The epic heroes of ancient literature are warriors and they are men of faith. Achilles, Hektor, Odysseus, Aeneas: they believed in the supernatural, they had certain ideas about the nature of the divine, they engaged in religious rituals and practices meant to appease the gods and win their favor. Aeneas is described by Virgil as being “patently pious,” pietas being a Roman virtue that meant duty to man, God and country. The faithful and pious would be rewarded by the gods, often with military victories. The gods could be violent, deceptive, and vengeful; to be godlike was to partake of the awful power of the gods, to exercise might. When these heroes succeeded in battle, they believed the gods were on their side; when they lost, they assumed the gods had forsaken them. They had faith, but a certain kind of faith in a certain kind of god. The pagan gods could be drafted.

Desmond Doss was a social pariah until he became a kind of mascot. In Okinawa his Bible, his personal prayer, and his faith were no longer things to be laughed at but to be embraced and rallied behind. It is a fact that the third big siege on Hacksaw Ridge happened on a Saturday, May 5, 1945. The men asked Desmond Doss if he would go with them. Doss said maybe, but he would need time to pray about it first. The story goes that the whole unit, or company, was held up on account of Desmond Doss needing to pray. They waited, and hoped. After praying Doss decided that this was the kind of work he could do on a Saturday and he went with them. Perhaps I was being overly defensive, but in the film they almost made this decision look like a compromise. It wasn’t. Desmond Doss was tempted on various occasions to kill in defense of self or others, but he didn’t: He said that if he compromised once, he was likely to compromise again. The closest he came was when enemy troops threw a grenade into a ditch where he was trying to help some wounded men: He did pick it up and throw it back out. His decision to go with his unit on that Saturday was not a compromise: It was perfectly in line with the story of Jesus healing on the Sabbath.

On that day they took the ridge. Many people attribute this victory to “faith,” either the faith of Desmond Doss or the faith he stirred in others after they began to believe that he had something like the power of God behind him. What’s wrong with this picture?

In the film, it appears that the very same God who Desmond Doss was praying to, who Doss believed would tell him, “If you love me, you won’t kill anybody,” who Doss believed he was glorifying with his works of courage, compassion, strength, and love, and who may have helped Desmond Doss to comfort, heal and save all those people, is the very same god who then turned around and helped Doss’ comrades to burn Japanese people’s faces off. If we are being honest about it, these are two different gods, and two different faiths. It is rare that they are seen in such stark relief as they are in Hacksaw Ridge.

Where one asks, “Please, Lord, just let me get one more,” and means save one more life, the other asks, “Please, Lord, let me get one more,” and means take one more life.

Where one says, “Love your enemies,” the other says, “Protect your friends.”

One says “Put down thy sword,” the other says “Pick it up.”

Where one says, “Love the Lord your God with your whole heart, whole soul, whole strength, and whole mind,” the other says, “Hate your enemy with your whole heart, whole soul, whole strength, and whole mind.”

One preaches against enmity, the other assumes it.

To help the enemy in one is considered love, to help the enemy in the other is considered treason.

Where one relies on the power of prayer, trusting completely and totally in Jesus, and willing to love nonviolently both friends and enemies until death, the other relies on the power of violence, trusting in government and is willing to kill enemies even unto death.

To live in the spirit of one of these gods is to bring about love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, faithfulness; to live in the spirit of the other is to bring about what we see happening on Hacksaw Ridge.

The Catholic Church tries to tell us that these are the same faiths and the same gods, two sides of the same coin if you will. What makes this film so important is that it gives us a concrete portrayal of a larger conflict that has been going on within Christianity for 1,700 years, not only among different sects and churches but also within Catholicism itself. In “A Harvest of Justice is Sown in Peace” (1993), the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops tells us: “The Christian tradition possesses two ways to address conflict: nonviolence and just war.” Where the Church sees a “dual tradition,” more and more people are beginning to see a house divided against itself. Insofar as the Catholic Church “possesses” the tradition of nonviolence, we agree with the Protestant denominations that have come to be known as the “peace churches” (The Quakers, Mennonites, etc.), but insofar as we teach what – frankly — Jesus never taught, by word or deed, namely, Just War Theory (now called Just Defense Theory), we part with them. The Catholic Church tries to tell us that there is no conflict between these two ways of dealing with conflict, that these two ways are not opposed to one another, nor is either way opposed to the Way of Jesus, in whom we Christians live, move, and have our being, that they are separate but equal, equally holy, equally good, equally acceptable. Yet, should one dare to speak out in favor of nonviolence, one would be no more welcome in the Catholic Church than Desmond Doss was in his rifle company. Trust me, I know!

This conflict is currently playing out at the highest levels of the Catholic Church. In April of 2016, the Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace at the Vatican and the international Catholic peace organization Pax Christi held a conference, called “Nonviolence and Just Peace: Contributing to the Catholic Understanding of and Commitment to Nonviolence” and included 80 participants from around the world who represented a broad spectrum of experiences in peacebuilding and active nonviolence in the face of violence and war. The participants called on Pope Francis to consider writing an encyclical letter, or some other “major teaching document,” reorienting the church’s teachings on violence. The “Just War” Christians have been freaking out ever since in fear that the Holy Catholic Church, under the “leftist” leadership of Pope Francis, will abandon the teachings on Just Defense, which everyone knows provides a crucial loophole in Jesus’ teachings, through which the Christian can ensure the earthly protection of himself, his family, his friends, his country. It would be a nightmare to deprive Christians of recourse to violence, right? They would be sitting ducks with nothing but their “faith” to protect them in a hostile and violent world. And I believe in this context the Just War camp would put “faith” in quotation marks, because what kind of faith is that stupid and foolish?

Hacksaw Ridge is indeed a film about faith, but not in the way the publicists meant it. As Jacques Ellul puts it: “The appeal to and use of violence in Christian action increase in exact proportion to the decrease in faith…Unbelief is the true root of the Christian championship of violence.”

Let’s hope that the film Hacksaw Ridge can teach American kids what the Catholic Church has failed to teach them. One of my students, after watching the documentary, exclaimed: “And he wasn’t even a Catholic!” This sweet child imagined that someone so good and so holy could only be the product of the one, true faith. It took my whole heart, my whole strength, my whole mind to refrain from replying sarcastically: “Thank God for that, because if Desmond Doss had been raised Catholic, he would have had little to no chance of becoming Desmond Doss.”

Copyright © 2016 Ellen Finnigan

Talking to Christians

My fellow Radicals and Subversives in Christ: I am so very glad to be with you!

Why do I refer to you this way? I know that those words may make some of you uncomfortable. I assure you that that is not my goal.

My point is simply this: The One that we are privileged to follow was and is the greatest radical and subversive who has ever walked on the surface of planet Earth.

Did he support the socio-economic and political status quo of his time? Hardly. He taught and demonstrated a radical departure from the social and political systems established by human beings. He actively subverted The System of Empire. In response to his radicalism and subversiveness, he was captured, convicted and tortured to death by that Empire.

Why was he a threat to The Establishment? I suggest that his primary threat was in his challenge to their assertion that they were God. Jesus countered that only God is God and that no human political or military leader or system is any sort of god at all. That posed a major threat to their power base. Therefore “The System” moved to eliminate this threat.

What does this mean for us now?

We are called to follow Jesus. He didn’t ask us to adore him or worship him. He told us to follow him. How can we interpret this directive? We can follow his example behaviorally. We can do our best to act as he did. We can follow his teachings and do our best to cultivate an internal attitude similar to his and practice corresponding external behavior.

I believe that following Jesus means following his path of Radical Love. What is radical about his kind of love? At the Last Supper, he told his disciples to “Love one another as I have loved you.” This is his instruction as to how we are to love each other (and love ourselves). He did not direct them (or us) to love any old way. He specifically tells them (and us) to follow his example and do it his way.

So what does it mean to love the way he taught and demonstrated?

He tells us to love those who hurt us. He tells us to turn the other cheek to those who have hit us already. He tells us to love our enemies. Even as he is being tortured to death on the cross he expresses: “Father forgive them. They know not what they do.” He provides a live demonstration even as he is dying. His way of loving is so counter-intuitive, so alien to us. It would seem that he wants us to actively forgive and love everyone who hurts us.

When we use the words “radical” and “subversive” it’s important to ask: A radical departure from what? Attempting to subvert what existing system or situation?

I would argue that the radicalism and subversiveness of Jesus was and is this kind of “movement” away from the Violence of Lies and toward the Reality of True Love. It is the conscious subversion of the idolatry of worshiping The-State-as-if-it’s-God.

Does this mean that we are called to do likewise? I think it does. I think it means that we need to recognize the various ways that each of us is invited or coerced into deifying and worshiping phony gods in our everyday lives.

Who and what are these phony gods?

Who are the individuals that are promoted as heroes in the public eye? Who are those that are advertised as great and powerful that the rest of us are supposed to cheer for and adore? What are we repeatedly told to buy and buy into? What are we directed to glorify by those with materialistic power? What are the institutions and products that are endlessly marketed as “must have” if we are to be acceptable as human beings?

Who wants us to be afraid?

Phony gods.

If we choose to follow Christ, we commit to the path that is a radical departure from the System of Empire and the lies that sustain it. We commit to a path that is a radical movement toward the Unity of Real Love. We express and accept the “Yes!” to who and what we truly are: Manifestations of Love.

If we choose to make this claim, we can expect to be labelled as “subversive” by the world of phony gods. If we take this stand, we should expect The System of Empire to react with violence of some kind. That is consistent with its philosophy. We must be prepared for this reaction.

No empire likes to be told that its “new clothes” are an illusion!

My fellow radicals and subversives, we have choices to make.

We can choose to conform to the System of Empire and enjoy the materialistic comforts that come with it. This option requires behavioral obedience to The Establishment as well as psychological acceptance of its worldview. We must do and think and feel as we are told.

There is another choice.

We can choose to follow Christ’s Way.

This means letting go of the Temptation Traps of the human ego. These are traps like: “I want what I want when I want it” and “I”m more deserving than you” and “Us vs. Them”. It means accepting discomforts we may be unaccustomed to and suffering rejections and criticisms from both strangers and loved ones. It means embracing a lifestyle of all-inclusive compassion and forgiveness. It is a matter of choosing what is real instead of a hollow fantasy. It is a matter of choosing love over fear, freedom over slavery.

It is the choice of redemptive nonviolence over non-redemptive violence.

My fellow Radicals and Subversives in Christ, we have choices to make.

Letter to a Terrorist

Desperate One,

I want you to stop killing and destroying.

What do you want?

That is the question that many might ask you if they took the time.

It is obvious that you want others to be afraid and to suffer. The real question is: Why? What do you hope to achieve by terrorizing? Your actions are a means to an end, are they not? Your willingness to die for your cause points to some higher purpose, some worthy goal deserving of great sacrifice. Have you made this clear? Have you expressed what you really want? If you have, I have not heard you. If that is the case I apologize. Please tell me again.

There are better ways for us to problem-solve.

There are some who would prefer to deny the truth of your humanity. There are those who want to quickly dehumanize you into nothing more than a vicious animal that needs to be exterminated. Frankly, that’s a big mistake. It’s a blinding perspective born out of fear and ignorance. The real truth is that you are just as human as I am.

That’s what makes you really scary. You show me a part of myself.

It would be so much easier if you were actually a monster. If you were a monster then I could believe that I am not like you. Such a fantasy! The truth is that neither of us is a monster and yet we are both capable of such monstrous behaviors, aren’t we? The other side of the coin is equally true: You and I are both capable of rising above our destructiveness. We are both capable of living up to our Higher Nature. You and I need to get past the limiting illusions of our Fear and Anger which keeps us living a Lie of Separateness. We need to move into the truth of our Real Unity and the Logical Compassion that is its hallmark.

Once we establish our common ground we also have to acknowledge that each of us has legitimate needs and desires. Many people skip over this part of the story. Many just assume. They assume that you are only a thoughtless killer lacking any shred of decency or conscience. That makes it much easier for people to hate you and to support those who want to kill you. It’s so much easier for people if they think you are so different from them. If they realized that you basically want what they want it would make hating you a lot more difficult.

You have a family and friends just like I do, don’t you? I’m guessing you want to be happy and live a long and meaningful life, just as I do. You probably want to see your children grow up to be healthy and happy in their lives. You want to enjoy your grandchildren someday, don’t you? I think we are probably much more alike than we are different. So why is it so much easier to focus on our differences? Are they really more important than what we have in common?

So what is it that motivates you to kill and destroy? What makes you willing to commit suicide for your cause? Martin Luther King once said: “a riot is the language of the unheard”. Perhaps it can also be said that acts of terrorism are the language of the unheard.

If I start to hear you and understand you, will you stop what you’re doing?

I am desperate, too.

I’m desperate for our collective madness to stop. I’m desperate to end the suffering that we both keep manufacturing. I know I need to take a good, hard look in the mirror and see how I have been contributing to our shared problem. I’m a fool if I think that it’s “all your fault”. I need to take full responsibility for my part. I want you to do the same. We are part of the same family and the highest responsibility of all family members is to love each other.

It is high time that we both live up to that responsibility.

The Real “War on Christmas”

I am somehow both astonished and not at all surprised at the so-called “War on Christmas” that has again surfaced in the public consciousness. This time around the epicenter of the quake is a red paper coffee cup. In years past I recall that the storm was all about whether or not it was appropriate for people working in stores to wish their customers “Merry Christmas”.

There is a Real War on Christmas that’s been going on for a long time. It’s obvious and it’s subtle. It’s taking place thousands of miles from here and it’s taking place a very short walk from wherever you are. It’s all around us and it’s within us.

We declare War on Christmas when accept that buying things in stores is what the season is all about. When we accept that “that’s just the world we live in” and conform to the social expectation that says “shop ‘til you drop” we declare War on Christmas. When we wait in line for the hour the door opens to storm into some big box store for Black Friday “deals” we declare War on Christmas. The ensuing mad rush to get something off the shelf before someone else can is the modern blitzkrieg in the War on Christmas.

We engage in War on Christmas when we hold onto our resentments and refuse to forgive on the grounds that those who have wronged us don’t deserve it. We stay at War with Christmas when we keep our hearts hardened and cling to our belief that we are “right” and anyone who doesn’t see it our way can take a long walk off a short pier. When we don’t consider the equal dignity of all who are not practicing Christians we also guilty of waging War on Christmas. We perpetuate this war by the arrogant assumption that ours is a “Christian Nation” and if someone doesn’t have a membership card to the “club” they’ll just have to scrape by as best they can. Or they are told to “go back to wherever they came from if they don’t like it here”. Allegiance to the “us vs. them” propaganda is jet fuel on the fire in the War on Christmas.

We put an end to the war on Christmas when we slow down enough to smile and say a kind word to people we don’t know as well as to those we love most dearly. We put an end to the War on Christmas when we remember that every human being everywhere is our brother and sister. We end this war when we live up to our birthright as creatures made out of love, made for love, and designed to love each other and ourselves. We end the war when we no longer allow ourselves to be blinded by our hatred and fear. We end it when we connect to the truth that every one of us is part of and belongs to all of creation. Peace is ours when we realize that we are all part of the same crazy, wonderful, and mysterious family.

So drink your coffee from any cup of any color that makes your heart sing. Wish anyone you like a “Merry Christmas”. Or smile and wish them “Happy holidays”. Or if you want to be particularly subversive you can wish people “Happy Holy Days”. Or just smile and wish them a “Good day!”. But don’t mistake Christmas for something that comes from a coffee shop or a retail store.

An Invitation to All Catholic Killers

Recently we here at Catholics Against Militarism made a small effort to counter a very troubling article promoting militarism which appeared in the National Catholic Register. The article, by Wayne Laugeson, was provocatively entitled Catholic, and Killing for a Living, and it was about the “hot topic” of American snipers.

Our email drawing attention to the article and asking for people’s help appeared on the Lew Rockwell blog.

I would like to make a few comments about what I consider to be the most remarkable and disturbing aspect of the article — the emphasis on the Christian, pro-life credentials of the snipers. My comments are directed strictly at pro-life Catholics and Christians who join the military, not police or law enforcement snipers who are in a completely different situation. It is a serious weakness of the article that the author conflates the two different types of snipers.

The basic premise of the article is that being an “American sniper,” including participating as a sniper in America’s foreign wars in Iraq and elsewhere, is all about protecting innocent life and fighting evil, just like being against abortion and part of the pro-life movement.

Jack Coughlin, the Marine Corps sniper who is the principle subject of the article, is a “devout pro-life Catholic.” The people Jack killed were “ruthless killers,” and being a sniper is about saving innocent lives.

Butch Nery, another devout Catholic and Vietnam veteran says that an American sniper defends the “country and the oppressed” and “helps disadvantaged individuals … survive evil aggression.” Nery also says this:

“When you are overseas, and you see some of what the enemy does to innocent women and children, you don’t have any questions about the morality of a sniper’s role in the overall mission.”

And, we are told, police sniper Derek Bartlett believes that the Bible contains many justifications of violence in defense of innocent life in war and peace.

Dave Agata, a “nondenominational Christian,” says that snipers are “mostly a moral pro-life community” and that “an American sniper is someone tactically trained to save innocent lives.” Mr. Agata makes the most dramatic statement about abortion in America:

“In this country, you can take a young girl to a clinic and pay some butcher to take the life of a baby.”

But for Catholics, of course, this is actually an understatement. Catholics believe that abortion is murder and that this “butchery” has been going on for decades and has taken millions of innocent lives. It is often described correctly by pro-life activists as a holocaust, a genocide and mass murder. Consider that in 2012 alone, the Planned Parenthood clinic on Commonwealth Avenue in Boston, where I live, performed nearly 7000 abortions.

It seems to me that our first obligation is to defend the innocent and fight evil right here in our own backyard. If we had a decent, healthy society then Dave Agata’s “butcher” would be arrested and prosecuted and prevented from doing further harm. But who is protecting this ruthless killer?

It is, without a doubt, the U.S. Federal Government that is the most powerful defender and promoter of the abortion industry in our country. If it wasn’t for Roe v. Wade, which overturned state and local authority and made abortion the law of the land for hundreds of millions of people, we would have some state and local governments that would restrict and even abolish abortion.

American Snipers, I am ready to take you at your word that you are devout Catholics and/or pro-life Christians who want to defend the innocent and oppose evil in the world. We are of like mind on this matter. The only thing I hate more than war is abortion. But I believe you are making a terrible mistake. You are devoting your talents and courage and sacred honor to assisting and strengthening our great enemy, the U.S. Federal Government. This government is the enemy of the unborn and the innocent, and I would add that it is also an enemy of peace. Is it that hard to imagine that this amoral, anti-Christian entity which enforces the unjust, diabolical abortion law, might also be engaging in unjust wars? This question is not honestly discussed in the article.

If Catholics and other pro-life folks were willing to non-violently resist Federal power and challenge it with the local authority of states and cities, Church and family, we might be able to establish a beachhead in North Dakota or Alabama, or even in “liberal” Massachusetts and Rhode Island, the two most Catholic states in the union. We might create an example of a state or city with genuinely Christian pro-life laws and values that might spread to other places. But this can never happen as long as good Catholics are so submissive to and entranced by the immensely powerful and increasingly totalitarian central government and its armed forces. In effect, America’s perpetual wars and suffocating militarism serve to distract American Catholics from the fundamental evil of abortion which exists at the core of our society. In order to make inroads against the culture of death, the Catholic love affair with the military and the state must end.

Ultimately, both literally and figuratively, between us pro-life Catholics and the walls of that Planned Parenthood clinic stand the U.S. Army and the Marine Corps.

So obviously I have some serious disagreements with the Catholic snipers and other Catholic soldiers regarding the foreign wars of the US military, but our Catholic Faith and our pro-life commitment should enable us to find some common ground and possibly even work together. I’d like to hear from Jack Coughlin or Butch Nery or any “Catholic killer” who shares their viewpoint. Just post a comment to this blog or use the contact page and I’ll get back to you and we can have a private conversation. Perhaps we can even meet face to face at some point and talk, man to man, brother to brother, Catholic to Catholic. You never know what might come out of such a meeting, since “the Lord works in mysterious ways.”

Recommended further reading:

Christians and the Pro-Life Ploy

Do Heroes Go to Heaven?

Over the past decade or so I have witnessed some disturbing trends at church. One would have thought that our Lord Jesus Christ had, himself, worn a government-issued uniform, given how much reverence, gratitude, and appreciation we are led to collectively express for these folks during Mass. At first, it was a weekly prayer “for the troops,” which is fine. There is no human being, alive or dead, who doesn’t need prayers.

However, we never prayed for the innocent civilians in the countries Americans had invaded, who were killed, maimed, and tortured in far greater numbers than Americans.

We never prayed for the loved ones they left behind, the widows, the orphans.

We never prayed for the refugees.

We never prayed for our enemies.

The secular state holidays have become occasion for military remembrance and honorary tribute. On Memorial Day and Veterans Day, the church bulletin includes a message of thanks to veterans for protecting Americans’ freedom, which sends the message to churchgoers that American “wars” abroad have something to do with the Bill of Rights here at home, and the wars are therefore necessary and just (a dubious notion at best). At some point, militarism began to invade Christmas with camouflaged Christmas ornaments and patriotic displays upstaging the Eucharist.

In the last year, the Catholic Church has expanded its prayers to allow more folks in uniforms to get in on the prayer action. In addition to (or in lieu of) praying for military servicemen and women, Catholic Churches are now offering weekly prayers on Sundays for all “first responders.” One wonders how this became a national “thing.” (I have heard it in several states). It seems to mesh nicely with the overall message in the mass media that we are all on the brink of ruin all the time, threatened by an inexhaustible number of enemies and looming crises, and should live in fear and trembling awaiting the next crash, attack, disaster, or pandemic; thus we owe an infinite debt of gratitude to those who offer us safety, order, and protection in such a precarious and nefarious world. (Hm. Who benefits when we have a nation of nervous Nellie’s?)

Things seem to have reached a new threshold with American Sniper. We now have American priests coming right out and saying things in the media like: “Chris Kyle was an American hero.”

The primary concern of the Church is the salvation of souls. Christians are concerned with holiness, not heroism. Whether Chris Kyle was an American hero is a secular idea and a moot point, and a strange pronouncement for a priest to make, unless that priest is willing to ask the questions that naturally follow: Does heroism lead to holiness? Do heroes go to heaven? Before you write me an email vilifying me as a “liberal” who “hates” soldiers for asking these questions, let me say: I do not know if “heroes” go to heaven. Nobody knows. Only God can judge the human heart. What I’m saying is: it is dangerous to pretend that they automatically do. It’s also dangerous to pretend that the question I am asking is, itself, a moot point.

When churches and religious leaders constantly adore, praise and worship those who wear uniforms, carry guns, and embody secular ideas of heroism, it leads to misunderstanding and moral confusion among the faithful. People begin to equate this image of heroism with holiness, especially children. If you don’t believe me, all you have to do is take a look at www.nogreaterloveart.com, where uniformed government agents are depicted with angels’ wings, angels of course being spiritual beings who are known for their ability to guard and protect. All you have to do is look at the “Soldier’s Stairway to Heaven,” very popular on Pinterest, or license plates and t-shirts that quote John 15:13 and hold up the service of the soldier as being second only to the “service” of Jesus. There is an idea that if you have fought in a war, you have “served your time in hell”; soldiers therefore go straight to heaven. But is such an idea spiritually and theologically acceptable? Does God offer bypasses?

Heroism and holiness have many things in common: They both require strength, courage, devotion, fortitude, self-sacrifice. But all of those qualities could be attributed to people fighting for ISIS just as well, even faith. According to the Catechism of the Catholic Church: “The way of perfection passes by way of the Cross. There is no holiness without renunciation and spiritual battle.” There is no holiness without renunciation; that does not mean that every act of renunciation leads to holiness. The way of perfection requires hardship; not all hardship helps us on our way to perfection. In short, not all suffering is redemptive.

It is easy to look at someone like Chris Kyle, who believed he was doing the right thing, and to see him struggling with what he believed was his duty, to see him suffering because of it, and to believe that this means he must have been fighting the good fight. But not every spiritual battle necessarily involves “the spiritual progress that tends toward ever more intimate union with Christ,” or in other words holiness. Chris Kyle surely had a conscience, but a struggle with the conscience only shows that you have a conscience; it is no proof that you end up coming to the right conclusions or doing the right thing. While priests like Fr. Trigilio can confidently assure us that men like Chris Kyle are American heroes, there is good reason to suspect that many of these “heroes,” despite their suffering, self-sacrifice, service to country, and good intentions, lose the spiritual battle, as evidenced in the depressing number of veteran suicides. How can we look at those numbers and not see that something is very wrong here? Look at the way Chris Kyle died. Obviously, our idea of heroism is very flawed if it can lead to so much despair, but I don’t expect to see Matthew 26:52 showing up on a lot of t-shirts and license plates any time soon.

Holiness never leads to despair; it leads to peace and joy. It leads to the kingdom of heaven. Saint Maria Faustina Kowalska wrote in her diary: “Pure love never errs. Its light is strangely plentiful…It is happy when it can empty itself and burn like a pure offering. The more it gives of itself, the happier it is.” If the service of the soldier were a pure form of love, the kind of love of which there is “no greater love,” then wouldn’t multiple tours of duty just make soldiers happier and happier? I saw American Sniper. I’ve seen a lot of Iraq and Afghanistan war documentaries. This doesn’t seem to be the case.

It is important to understand the differences between secular ideas of heroism and religious ideas of holiness, lest we be led astray by sentimental notions and superficial understandings or, worse, lest we begin to call evil good. The thing about virtue is that, to paraphrase C.S. Lewis: Every vice has a trace of virtue in it, while virtues are entirely devoid of vice. One problem with praising the secular idea of heroism in church is that we cherry pick virtues that we like to see in “heroes,” but we fail to take into account the bigger picture of holiness to which every Christian is called; there is a risk that we might only be identifying the traces of virtue in a larger sea of vice. Chris Kyle was a strong, courageous, and confident man, who felt very justified in killing all of those people in American wars and said he was ready to meet his maker, that he was sure God wouldn’t count any of those kills against him as sins. But self-assurance is not a virtue; the morality of an act does not increase along with our level of personal comfort. If there is one thing that stands out in the writing of the saints, it is a profound and troubling knowledge of their own sinfulness. Along with holiness comes a greater sensitivity to the will of God and a greater awareness of sin. Even the smallest offenses against God caused the saints great agony and pain, and I mean the smallest offenses. The only thing they are as assured of as their own sinfulness is God’s infinite mercy. Does heroism likewise lead to a greater sensitivity to the will of God and a greater awareness of one’s own sinfulness?

There are particular mortal sins that are so evil that they are said to be sins that “cry to heaven for vengeance.” Murder (Gn 4:10) is one of them. There are mortal sins that harden a soul by its rejection of the Holy Spirit: They are despair, presumption, envy, obstinacy in sin, final impenitence, and deliberate resistance to the known truth. Perhaps Kyle’s 160 “kills” are signs of courage and fortitude, or maybe they are a sign of something else. Maybe American Sniper shows us what happens when the heart and the soul are hardened. Maybe it shows us that “sin creates proclivity to sin; it engenders vice by repetition of the same acts. This results in perverse inclinations which cloud conscience and corrupt concrete judgement of good and evil. Thus sin tends to reproduce itself and reinforce itself…Thus sin makes men accomplices of one another and cause concupiscence, violence and injustice to reign among them” (CCC 1864-1868). Is there a better description for what happens in war? Maybe Chris Kyle was courageous, or maybe he was just obstinate. Maybe his self-assurance stemmed from a deep awareness of the will of God, or maybe he was just presumptuous. Maybe he wanted to protect America, or maybe he was driven by a desire to avenge the deaths of his comrades. Again, I don’t know. But neither does Fr. Trigilio. God only knows.

The one religious holiday that seems impervious to encroachment by celebration-of-all-things-military is Easter. There is just no way one can glamorize the soldier or equate military service with heroism after meditating on the Stations of the Cross. I gathered some images that show the soldiers in the story of the Passion of Christ as portrayed in various works of art. Not very heroic. Looking at these images, one can’t help but be reminded that the spirit at work in these soldiers was not the spirit of God but the spirit of Satan. It is a very different spirit. They have nothing, absolutely nothing in common. Each one is recognizable for what it is.

The religious leaders hated Jesus, but they turned to the power of the state. It was the Roman soldiers that carried out the act of crucifixion. I’m not saying the soldiers bear sole responsibility, but what is so frightening is that these soldiers, presumably, had no personal animosity towards Jesus nor any cause to hate him (as the religious leaders did)—and still, what cruelty they were capable of! The physical torture they subjected Jesus to, which was required to carry out the orders and enforce the punishment, which almost everyone seemed to believe was “necessary” for “justice,” was bad enough, but what do we make of their mocking and humiliating Jesus, something that was not required, not ordered, and definitely not necessary? It betrays a deeper, more sinister evil, a meanness that did not grow from outrage over the “enemy’s” supposed “savagery” or transgressions; it was a meanness seemingly already there in their hearts, just waiting for a chance to expend itself, to be loosed. The crowd who cried “Crucify him! Crucify him!” gave them that chance.

In the painting entitled “Christ with Mocking Soldier” by Carl Bloch (1834-1890), the character of the soldier is depicted as practically drooling with hatred. This is no reticent and regretful man shamefully escorting a harmless innocent to his death for fear of disobeying orders. This is a mean man, a shorter man, an older man, weaker in both body and spirit than Jesus, but he happens to have a certain kind of power: the power of the state, which is the power of this world, which is the power of violence, which is a kind of power that Christ refused and told his Apostles to renounce (“Put down thy sword”). The soldier relishes it. In the painting we see a certain spirit at work.