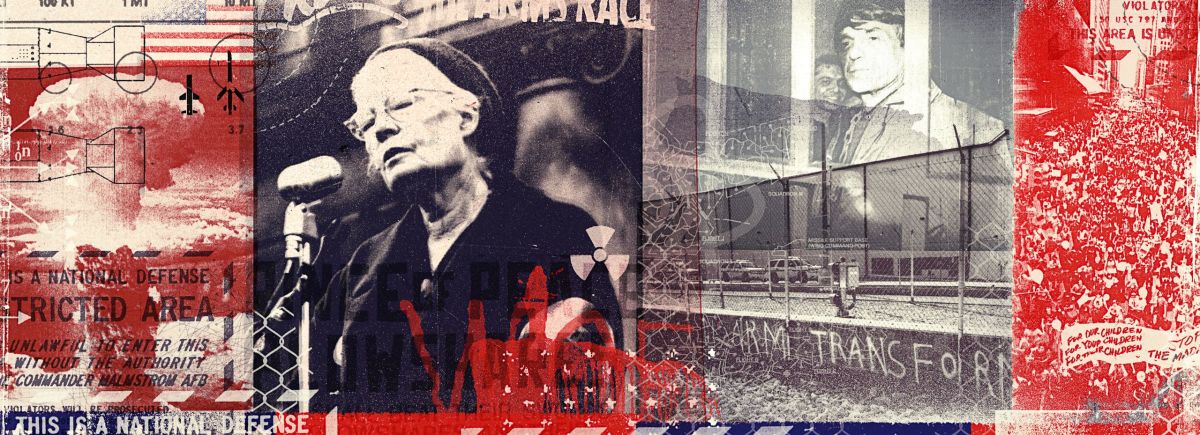

This chilling poem by Cistercian monk, writer and poet Thomas Merton offers a dramatic portrayal of SS Officer Rudolf Hoess.

This poem was published in 1961 by Lawrence Ferlinghetti for the inaugural edition of “Journal for the Protection of all Beings.”

The music that accompanies this piece was composed and performed by Henk van der Duim of Zero V.Chant to be used in Processions around a Site with Furnaces can be streamed using the media player above. A CD quality mp3 audio file is available for download here.

Chant to be used in Processions around a Site with Furnaces

How we made them sleep and purified them

How we perfectly cleaned up the people and worked a big heater

I was the commander I made improvements and installed a guaranteed system taking account of human weakness I purified and I remained decent

How I commanded I made cleaning appointments and then I made the travellers sleep and after that I made soap

I was born into a Catholic family but as these people were not going to need a priest I did not become a priest I installed a perfectly good machine it gave satisfaction to many

When trains arrived the soiled passengers received appointments for fun in the bathroom they did not guess

It was a very big bathroom for two thousand people it awaited arrival and they arrived safely

There would be an orchestra of merry widows not all the time much art

If they arrived at all they would be given a greeting card to send home taken care of with good jobs wishing you would come to our joke

Another improvement I made was I built the chambers for two thousand invitations at a time the naked votaries were disinfected with Zyklon B

Children of tender age were always invited by reason of their youth they were unable to work they were marked out for play

They were washed like the others and more than the others

Very frequently women would hide their children in the piles of clothing but of course when we came to find them we would send the children into the chamber to be bathed

How I often commanded and made improvements and sealed the door on top there were flowers the men came with crystals

I guaranteed always the crystal parlour

I guaranteed the chamber and it was sealed you could see through portholes

They waited for the shower it was not hot water that came through vents though efficient winds gave full satisfaction portholes showed this

The satisfied all ran together to the doors awaiting arrival it was guaranteed they made ends meet

How I could tell by their cries that love came to a full stop I found the ones I had made clean after about a half hour Jewish male inmates then worked up nice they had rubber boots in return for adequate food I could not guess their appetite

Those at the door were taken apart out of a fully stopped love for rubber male inmates strategic hair and teeth being used later for defence

Then the males removed all clean love rings and made away with happy gold

A big new firm promoted steel forks operating on a cylinder they got the contract and with faultless workmanship delivered very fast goods

How I commanded and made soap 12 pounds fat 10 quarts water 8 ounces to a pound of caustic soda but it was hard to find any fat

“For transporting the customers we suggest using light carts on wheels a drawing is submitted”

“We acknowledge four steady furnaces and an emergency guarantee”

“I am a big new commander operating on a cylinder I elevate the purified materials boil for 2 to 3 hours and then cool”

For putting them into a test fragrance I suggested an express elevator operated by the latest cylinder it was guaranteed

Their love was fully stopped by our perfected ovens but the love rings were salvaged

Thanks to the satisfaction of male inmates operating the heaters without need of compensation our guests were warmed

All the while I had obeyed perfectly

So I was hanged in a commanding position with a full view of the site plant and grounds

You smile at my career but you would do as I did if you knew yourself and dared

In my days we worked hard we saw what we did our self sacrifice was conscientious and complete our work was faultless and detailed

Do not think yourself better because you burn up friends and enemies with long-range missiles without ever seeing what you have done

Baghdad